Armin Steuernagel Transforms the Logic of Business one Company at a Time

As the pandemic has stood the world on its head, one of the debates which has been thrown wide open is that of the future of the economy. This article is part of PSJP’s inquiry into how markets can be made to work for the common good and how economies can be made to serve the general interest, rather than that of the few.

Steward ownership transfers leadership of a company to the individuals operating the company. It places purpose over profit and ensures longevity, good business as well as a diversified economy. The model is gaining traction in Europe. Armin Steuernagel explains why this is an approach the world cannot afford to ignore.

The classic, simplified company organigram is straightforward: at the top of the ladder sits the owner, followed by investors, the CEO, managers, and finally the doers also known as the staff. The owner has the final word, investors ensure and prompt growth, the CEO and managers steers the ship, and the staff work and implement. The ultimate goal is to maximize profits for the shareholders – the ones on the top of the ladder.

But what if the organigram was flipped on its head? What if the goal of a company was to maximize purpose? What if the doers were the owners?

These are a question Armin Steuernagel spends his days thinking about. A serial entrepreneur and the co-founder of Purpose, an investment fund/think tank consultancy, Steuernagel works to transform the way the world owns, invests, and creates profit.

“My focus is in rethinking ownership and supporting companies in transforming their shareholder geared motors to purpose-oriented engines. My work is about changing the very DNA of companies by transforming wealth ownership into steward ownership. In other words, transforming owners into stewards whose stakes go beyond ownership through wealth,” Steuernagel beings.

Two principles lie at the heart of the steward ownership approach:

1) Self-governance as a defining factor for enterprises: In the steward ownership model, control over the company remains within the company with the people steering the operations and mission of the company. In practice, this often means transferring control of the company to a trust ensuring that the company cannot neither be bought nor sold.

2) Profits generated are to serve the purpose of the enterprise: As per the steward ownership model, wealth generated by the business cannot be privatized. Instead, profits are to be used to serve the mission of the company and are either reinvested in the company or its stakeholders or donated to other causes. Investors and founders are fairly compensated with capped returns or dividends.

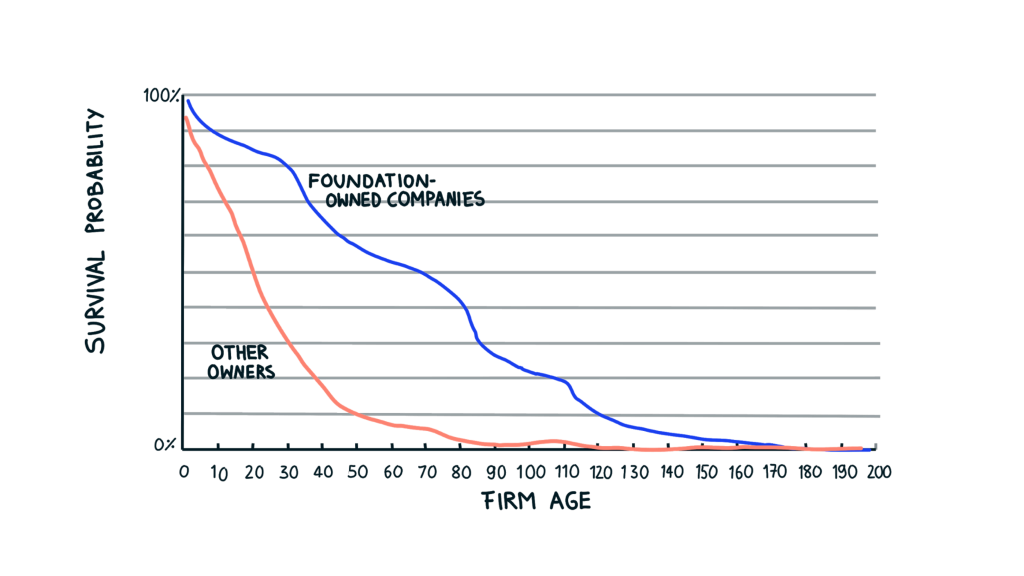

Steward Ownership far from a mission impossible is gaining traction. In Denmark, the combined market capitalization of steward-owned corporations represents 60% of the entire value of the Danish stock market. Often these companies are owned by foundations and have higher survival probabilities than conventional companies and lifespans that stretch across generations. Their success goes beyond the goodwill of the highest bidder and the wealthiest investor.

Makes Sense – Why Are We Not Walking the Talk

“When we started, we got a lot of ‘well this is not capitalism anymore, this is socialism’ toned comments,” Steuernagel recounts. Since the launch of Purpose half a decade ago, the team has supported 100 companies in moving from traditional forms of ownership to stewardship models. Even if the socialism card is no longer on the table, change is slow and the pace of progress is set by three hurdles: language, law, and culture.

“The first challenge is the simple fact that the vocabulary and language to describe stewardship barely exists. This leads to a lack of understanding regarding the concept itself and the possibilities it presents,” Steuernagel elaborates.

Words such as ‘foundation-owned’ or ‘employer-owned’ companies exist, yet their nuances are not the same as the ones captured by the notion of stewardship. The foundation-owned or employer-owned can have private beneficiaries and the latter can still be sold on the stock market. Foundation- and employer-owned companies often rely on the same incentive structure as traditional companies, even if ownership is distributed beyond direct shareholders. Questions regarding monetization thus lie at the heart of the steward-ownership model. A steward-owned company cannot be purchased, even if assets can be sold in order to maintain flexibility.

“Even if the words are not there, the idea is. We see many entrepreneurs and family businesses use the language of steward-ownership. When the will is there, our role is to give them the words and models to implement,” Steuernagel notes.

Despite the confusion of stewardship-jargon, the concepts are gaining traction.

“We started hosting small events in Berlin before the pandemic. These events were about how to reset the economy through, for example, new models of ownership. We had 1500 registrations for the first event. We have since struggled to find a technical solution that would allow us to cater to the interest we are seeing.”

The second factor slowing down demand lies in the legal frameworks regarding ownership and company structures. Legal structures tend to favor traditional forms of ownership thus guiding the operating models, decisions, and actions of the ones fueling growth – investors.

“The idea of a self-steered company is not the revolutionary part of stewardship. The revolution is in the fact that we are de-coupling money and power,” Steuernagel underscores.

“We are saying that power lies with people who are stewards. And this means that one cannot buy power – no matter how high you bid. Many investors believe that the more they invest the more influence they get. We are shifting this mindset from investors as owners to investors as enablers.”

“The idea of a self-steered company is not the revolutionary part of stewardship. The revolution is in the fact that we are de-coupling money and power.”

Armin Steuernagel

“We are saying that power lies with people who are stewards. And this means that one cannot buy power – no matter how high you bid. Many investors believe that the more they invest the more influence they get. We are shifting this mindset from investors as owners to investors as enablers.”

Armin Steuernagel

This brings us to the final, most challenging, hurdle – that of shifting the way the world thinks about ownership and investing. Even if investors and decision-makers are on board in principle, once interest transforms to contracts, investors start hitting the breaks.

“We might have an investor who is very onboard regarding the idea of stewardship and the investment opportunity at hand. But once they see that their investment has not bought the power they are used to seeing, hesitation and traditional ways of thinking kick in,” Steuernagel says.

According to Steuernagel the learned structures are at best shortsighted and at worst destructive for the company – and the investor. A self-steering company is a company capable of taking decisions based on the ingrained, hands-on knowledge held by the actual doers and experts of the company. In other words, steward-ownership renders the checks and balances of a company independent of the one writing the checks and gives decision-making power to the implementers.

Who Are the Trailblazers, Allies, and Sceptics

As in all movements, it is the presence and power of the followers that makes a novel idea mainstream. The reasons individuals and groups ascribing to the stewardship model are all but uniform. The Greens see the sustainability and responsibility angle, while the Conservatives and Liberals lean towards arguments related to enabling stable, diversified economies.

“The model of companies maximising their profits and outsourcing responsibility to the state, and the state having the role of writing the right laws assuming that there will be a fair share of profits, does not work anymore. The state can no longer be the kind police herding egoistic private players. The state is too slow and too stiff for this,” Steuernagel says. Governments are increasingly uncomfortable bearing the risk and ensuring the wellbeing of stakeholders on behalf of private actors.

This is a crux the steward-model addresses by in-sourcing responsibility. When law-makers see how the model integrates the moral of the company into the executive strategy of the company, party-leanings lose their weight. Stewardship is not necessarily about changing capitalism, it is about changing the drivers of capitalism by changing the drivers of private enterprises.

“Stewards are not, by definition, interested in short-term maximization of wealth, because the company cannot be monetized. They are interested in the long-term success of the company. This both is and is not a game-changer.”

Long-term thinking is neither fresh nor new. It is the classic way of thinking echoed in family-owned companies passed from generation to generation making decisions with time horizons spanning centuries. The stewardship model has thus been resonating among the family business scene for long and is gaining momentum specifically among family businesses struggling to find successors. By transforming into steward-owned companies these enterprises ensure that the company prevails even if it is no longer steered by a family. Even if the gene pool of ownership changes, values remain the same. When it comes to advocating for change, the biggest allies of Steuernagel’s work are indeed among the established, older entrepreneurs.

On the other end of the spectrum are the early adopters and start-up entrepreneurs with missions beyond making headlines with the biggest exit-value. Some of these trailblazers implement steward-ownership models right from the get-go or transform their companies early on to signal that they are walking the talk.

“A company owned by the doers signals to stakeholders and the public that they are here to stay. Steward-owned companies say: we are an entity that you can trust, we will not be bought nor fused anytime soon, and we will not become part of large conglomerates,” Steuernagel underlines.

In a volatile world were ownership and power is increasingly centralized among big players, trust is a competitive advantage.

What Next

The arguments speaking in favor of steward-ownership are compelling: it replaces competition with cooperation, leverages trust as a unique selling point, sets long-term prosperity as a priority, and helps the economy to decentralize. These are the levers Steuernagel is using to make his case.

“One of our goals is to create an investment landscape where steward-owned companies are their own asset class,” Steuernagel says, reflecting on his teams long-term goals.

“Our success is not only about how many companies we fund. Our performance is measured against how much money is invested into steward-ownership – by us or by someone else.”

Steuernagels commitment is unwavering, yet economists in general still refer to stewardship as a utopistic vision. The model simply does not fit contemporary incentive structures. But this is not the game Steuernagel is playing. He is not in for the short -term wins. His incentive is to build an economy that places purpose before profit. We are not talking about quarterly gains, but generational gains. The incentives for that are there.

Anna Tervahartiala is a communications and media professional with a background in sustainable finance, the humanitarian sector, and peacebuilding.