Sometime during a recent PEXForum conference, I wrote on my notepad that resilience has become the development sector’s new buzzword. Others have made the same discovery. PSJP’s new paper, Building Resilience in International Development lists a raft of references to the term in the later literature of development and it seems that multilateral organisations, foundations, think-tanks – you name it – have been all hastened to adopt the term.

Goal 11 of the SDGs, for example, aims to ‘make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable’, while Goal 9 urges us to ‘build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation.’ As usual, though, wholesale use has brought with it ambiguity. It’s become another of those words in development parlance that is used without a common understanding of what it means. (PSJP has been exploring some of these through it’s Key concepts series. The discussions on sustainability have revealed that depending on the context, ‘sustainability’ can convey any number of meanings including the seemingly contradictory notion of ‘redundancy’.)

But it’s all good….isn’t it?

Not that there aren’t plenty of definitions of resilience. To start off, let’s take one which contains many of the generally agreed elements as an illustration. The Stockholm Resilience Project characterises resilience as the capacity of a system to deal with change and continue to develop. In parallel, the term also has a longer and probably less hazy history in psychotherapy and it is characterised in a similar way by the American Psychological Association which defines it as ‘the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or significant sources of stress’. Note the emphasis on adversity here. Its use in development has increased significantly with the worsening of the climate crisis and the onset of the pandemic. In other words, it is often a defensive response and while it seems on the face of it, that encouraging and otherwise supporting the development of resilience among communities beset by disaster must surely be desirable, this should sound a note of caution. The Stockholm Resilience Project, while generally a votary of what it calls ‘resilience thinking’ cautions that ‘resilience is not a good thing in itself….resilience (particularly the ability to persist in a stable state) can be both positive and negative. Hence, sometimes the first step towards sustainable development is to reduce undesired resilience, in order to allow for transformation into a new alternate and improved state.’

Moreover, the PSJP paper mentioned above quotes Ruchita Chandrashekar, a behavioural health researcher and independent psychologist focusing on trauma and post-violence recovery: ‘as a result of this approach we enable a system where people from marginalized communities often blame themselves for their distress, when more of an emphasis needs to be placed on systemic structures that are at play.’

The politics of defeat

And for Neal Lawson of Compass in the UK, ‘resilience is ultimately a cul-de-sac…the fact that all we do now is go incredibly local and incredibly resilient just shows that we’ve lost the big arguments, the big debate about what kind of world and society we want to live, that’s what we’ve retreated to. To me, it’s completely and utterly the politics of eventual defeat.’

He believes that the notion of resilience can occupy people’s mental horizons to such a degree that it become impossible to see beyond it. ‘Very few people want to think outside of the box and the idea of resilience encourages that attitude…. Of course, there are immediate circumstances in which that needs to happen, but unless there is a parallel strategy, set of forces, arguments, etc which are going to stop the severe weather that’s beating us all down and get the sun to shine, it’s not gong to motivate or mobilise people and we’re going to end up in a diminishing cycle of groundhog day.’

Funders are often of no help here, either. It’s easy them to fall back on the language and attitudes of resilience ‘because it doesn’t mean asking the big structural, strategic questions about what is the good society and how do we get there? It’s just papering over the cracks and those cracks get bigger and bigger because you’re only addressing symptoms. And this speaks to the conservatism of the foundations, the NGOs, the givers who are not prepared to take on politics, whether that’s a small ‘p’ or a capital ‘P’. Unless you do that, you’re tying both hands behind your back which is what they continually decide to do.’

An indispensable tactic, but an unsatisfactory strategy

‘it can give people that sense of agency and purpose, but the question is how do you move from that to a much more strategic, transformative politics…..Resilience is necessary but not sufficient. It’s a tactical response, not a strategy.’

What about the idea that resilience is actually the springboard for developing greater agency, as PSJP’s paper on resilience argues? The paper cites the example of Tewa’s Hamro Tewa Gaun Ghar (HTG) and its response in the aftermath of the Nepal earthquake, using volunteers to help recovery of worst affected areas – providing training in new trades and skills, childcare and community development, etc. Their work suggests that ‘the experience of adversity can increase communities’ ability to cope and adapt.’ Lawson agrees that you need resilience and that ‘it can give people that sense of agency and purpose, but the question is how do you move from that to a much more strategic, transformative politics…..Resilience is necessary but not sufficient. It’s a tactical response, not a strategy.’

What you also need, he says is ‘to think about where those forces are which could be progressive and could produce a good society…we’ve just witnessed from civil society, but also in business and other sectors the emergence of a participatory form of deciding things and doing things. Some of that is about resilience and some of it is very local, but there’s a 21st century Zeitgeist which bounces off technology to link people up.’

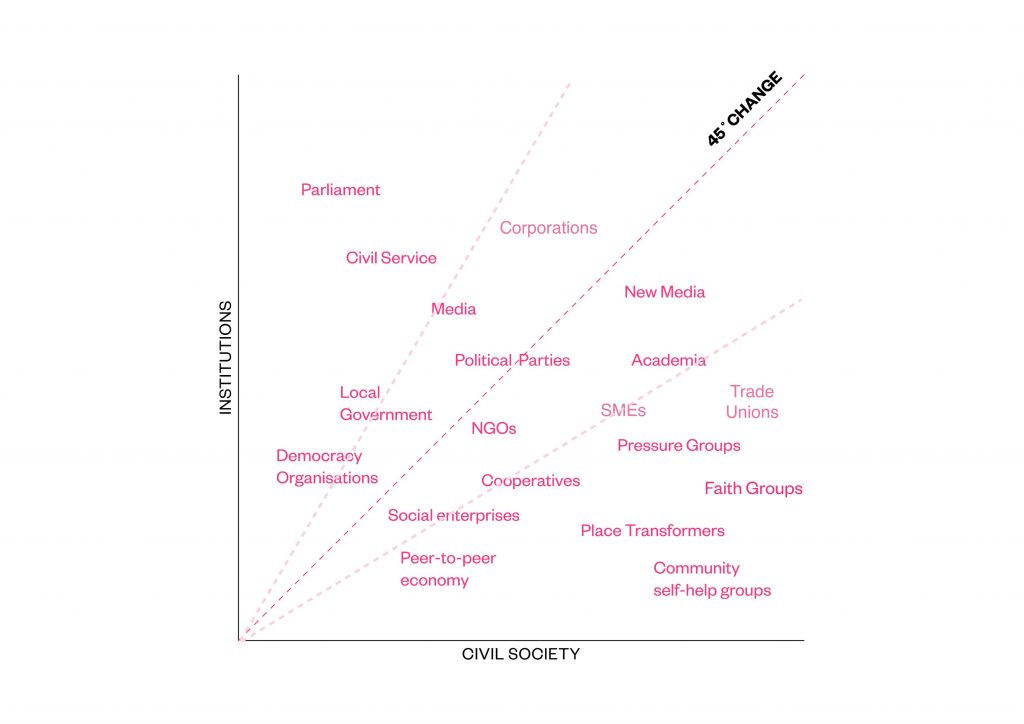

45 degree change

So where to, now? His organization, Compass, has devised the idea of 45 degree change. He explains: ‘it seems to us in that emerging sense of a co-created future, there is hope, but only if it’s allied to the role of the state. It won’t become the new paradigm without states supporting and facilitating it – funding it, making laws, supporting it rhetorically, etc. And our idea of 45 degree change is the diagonal meeting point of ground-up energy and collaboration and the vertical state and we think the really interesting things across the world happen when the two interact on that 45 degree line. How does the state support those movements and organizations who are doing this new participatory way of making change happen and there’s hope for a beyond-resilience future in that kind of alignment.’

And now might be the time. ‘Die Krisen räumen auf ‘ (‘Crises clear the decks’) as Swiss cultural historian, Jacob Burckhardt, pointed out. This has found many echoes lately in the idea that out of the Covid crisis, an opportunity has emerged. Lawson agrees: ‘Covid has created a global consciousness that wasn’t there before and the technology makes whatever we want to make of it possible.’ If we are to take the opportunity, we will need resilience, but a resilience that does more than develop the capacity to endure. It will also need to involve fostering the will and the means in groups and individuals to make the changes they want rather than adjust to those that are forced on them.

Andrew Milner is a freelance writer, researcher and editor specializing in the areas of philanthropy and civil society. He is a consultant to Philanthropy for Social Justice and Peace. He is also a regular contributor to, and associate editor of, Alliance magazine.