In this post Barry Knight takes a look at failed approaches to poverty in the UK, things worsening with the pandemic and ‘making life next to impossible for people towards the bottom of the income distribution, with minorities and women most affected’. He points out how politicians are ill-informed about poverty. As a result, mistakes are repeated. Employment-based political economies have receded and governments today favour ‘capitalists rather than the population as a whole’ and the whole system is driven towards a single goal – economic growth.

While Knight is talking about the UK, this is a universal problem. He makes suggestions about what might be done differently arguing for a new way of seeing and thinking from a broad range of actors including politicians, philanthropists, activists, economists… ‘requiring a leap in moral imagination that cascades through participants and filters through to social attitudes in society’. He provides examples of, as well as, calls for a diversity of approaches and ideas that draw on ‘different resources and sources of power, celebrating diversity, experimenting, testing, sharing learning, and building strength through connectedness’.

We have the ideas

It is now more than three years since Rethinking Poverty began to compile resources to support the development of a good society without poverty in the UK. Now, we believe that we have much of the raw material for the kinds of changes to enable us to thrive in the 21st century.

The immense range of the ideas shows that much energy from many quarters is being expended to help us escape from the mess that society is in. How do we organise these ideas?

A good place to start is Caroline Hartnell’s Creating a new narrative for a good society. This is a summary of a two-day retreat held in Letchworth in 2018. The location was symbolic, being the birthplace of the garden city movement. Their 100-year old dream was to create:

‘… beautiful green places which offer a wide range of employment, retail and leisure opportunities; supply a complete mix of housing types, including social and affordable housing; adopt zero-carbon design; implement sustainable transport; provide well managed and connected parks and public spaces; and provide a unique opportunity to offer people a better quality of life and more sustainable lifestyles.’

The retreat led to a framing of the society we want in three dimensions:

A fourth dimension, crosscutting all of these, is how to address the climate crisis, which must be embedded in everything we do.

A systems approach

This framing implies an intersectional approach, so that any single intervention is part of systems thinking that integrates diverse approaches such as green economics, new ways of doing democracy, people-led public services, community food systems, safety on the streets for women, basic income, community wealth building and many more inspirational ideas that can be found on the Rethinking Poverty website.

There are signs that some of these ideas are making headway. For example, the work of the Carnegie UK Trust on wellbeing has made progress in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The Preston Model inspired by CLES has influenced many local authorities. The Global Fund for Community Foundations’ campaign to #ShiftThePower is changing the face of international development.

The state is a blockage

At the same time, the overall response from the main political parties has been disappointing.

In a series of articles on Pandemic truths, Andrew Webster notes the ‘warped values of our way of life’, with the state locked into ‘sterile arguments’ while failing to address even the basic problems of our society. He suggests radical reimagining of the relationship between citizen and state: one that redistributes power, with public services enabling communities and citizens to better address the complex challenges we face. He suggests a series of programmes based on learning from People Powered Health, Sharelab, the Centre For Social Action Innovation Fund and the Upstream Collaborative. What these initiatives have in common is that they support people-powered innovations which put compassion, connection and collective power at their heart.

As we wrote at the beginning of the pandemic, the crisis was an opportunity to #BuildBackBetter. However, as things stand the government’s approach has been to Build, Build, Build, which is not the same thing at all. This has involved scrapping the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act, which according to Hugh Ellis, policy director of the Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA), will not only harm the environment but also damage local democracy.[1]

Meanwhile, January 2021’s Talking Points shows how close the UK is to becoming a failed state. The pandemic has exposed our weaknesses, making life next to impossible for people towards the bottom of the income distribution, with minorities and women most affected.

Efforts to ‘level up’ may push in the right direction but the allocation of £4.8 billion falls far short of the £78 billion recommended by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation in its 2016 report We can solve poverty. More fundamentally, I reviewed the history of area-based regeneration programmes in Rethinking Poverty, and found that funds of this type fail to make a significant impact on poverty. A new approach is needed but there is nothing in the Overton window that will deliver it.

The old system has failed

Our systemic failure is the starting point for this article. It takes a long-term perspective, examining why we have allowed poverty to persist in the UK despite having the means to end it. Poverty stains our society, and damages our people.

The pandemic threatens a return to widespread destitution. This presents a serious crisis for our society that our current institutions are ill equipped to deal with. The article makes suggestions about what we might do differently if we are serious about addressing the problem.

The article is in two parts. Part 1 reflects on the story of our failure to end poverty. Part 2 suggests what we might do about it from now onwards.

Part 1: Our failure

The tyranny of ‘now’ and ‘next’

Twenty-four hour news coverage means that our understanding of the world is shaped by a constantly swirling kaleidoscope of events. Events lose their currency quickly as new ones replace them. As I write this in May 2021, it is the Indian variant of Covid that dominates the news. Before that it was Palestine and Israel, and the 6 May elections have faded from view. By the time it is published, something else will be leading. It is as if we form part of a travelling circus that constantly moves on from place to place.

This means that politicians have little time to think. My experience of working closely with politicians is that they are so busy as they go from meeting to meeting that they live on the surface of constantly changing agendas, so long-term, chronic problems tend to be overlooked.

The problem of poverty is a prime example. Take for example the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s long-term strategy to solve poverty in the UK. When UK Poverty, Causes and Solutions was published in September 2016, it was the lead news item for 24 hours.

But who remembers this now? Four years’ worth of extensive research and strategic thinking has slipped into obscurity. In Rethinking Poverty, I noted the typical cycle of such reports. Poverty features in the news media when, for example, the UN Representative Philip Alston visits or when there is a two kilometre queue for a food bank in London. Activists express outrage but the problem is brushed off by the government of the day with standard defences of ‘much is being done’ or ‘lessons have been learned’. Then, the circus moves on leaving nothing behind.

Problems grow

At the launch of the new edition of Ruth Lister’s book Poverty in February 2021, Kate Green MP, Shadow Education Secretary and Labour child poverty spokesperson, expressed regret that ‘rich, informed discussion of poverty has disappeared from political discourse’. She said that ‘the issues around poverty were more widely understood 20 years ago among the “political classes”’.

Given that in 2020 the problem of poverty exploded across the UK, this is quite remarkable and gives credence to the common view that politicians are out of touch with ordinary people’s lives. It also means that the problem of poverty gathers and grows in the background untreated. We sleepwalk into difficulties and are ill prepared when we are brought face to face with the consequences of our neglect.

There is a cycle of compulsive repetition here and we never seem to learn. Forty years ago, Michael Heseltine wrote an internal cabinet report into the causes of the disturbances in Liverpool in 1981. It Took a Riot, which was declassified in 2011 under the 30-year rule, described Liverpool’s river as ‘an open sewer’. Its housing was ‘indescribable’, its employment figures ‘appalling’ and its social problems ‘severe’. The report recommended that ‘substantial additional public resources should be directed to Merseyside’.

Notwithstanding Heseltine’s exhortations, similar riots occurred across the country in 1985 and again in 2011. Yet, according to Robert Peston, elites in Westminster – himself included – were blind to the ‘helplessness felt by many’ when explaining the Brexit vote in Britain’s ‘left behind’ places.

Why does poverty persist?

Why does our society fail to deal with the problem of poverty when there is a mass of research data stretching back decades that would help us to solve the problem? To understand why, we have to examine our history.

Part of the answer is that we don’t believe we can solve the problem. Looking at the history of poverty, there appears to be one certainty: poverty has been a feature of every human society since time immemorial. As the Bible says: ‘The poor you will always have with you’ (Matthew 26:11).

This view was dominant until the end of the 19th century, but was challenged by a new generation of reformers and philanthropists. Charles Booth began the process with his 17-year study of Life and Labour of the People of London between 1886 and 1903. This was followed by Seebohm Rowntree’s two-year study of York between 1899 and 1901, published as Poverty, A Study of Town Life. These studies showed that people could not help being poor, since poverty was largely caused by illness, unemployment and old age. The age-old distinction between the deserving and undeserving poor was shown to be a fallacy.

Using these insights into the social causation of poverty, Joseph Rowntree set up three trusts in 1904 claiming that positive advance in the combined efforts of research, charity and politics could put an end to poverty by 1939.[2] A few years later, in 1909, Beatrice Webb, flanked by her lieutenants William Beveridge and Clement Atlee, launched her Minority Report of the Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and Relief of Distress 1905–09. At the launch she said: ‘It is now possible to abolish destitution.’ [3] Her proposals relied on state action rather than charity, and involved a managed economy,guaranteed minimum incomes and reform of the structures that produce inequality.

This was a sea change because it involved reframing the idea of poverty. Rather than seeing a category of person as in ‘the poor’, the reformers saw ‘poverty’ as a condition that anyone could be in. Rather than being a necessary feature of society, poverty was a contingent one, and this meant that it could be removed.

Progress

Gradually, this new perspective took hold, coming to prominence during the Second World War as all-party committees began to plan for the post-war world. The Beveridge Report of 1942 aimed to end the five great evils of want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness. Post-war policies were designed to guarantee full employment and to provide social security for all citizens. In the short term, this was highly successful. There was a marked reduction in poverty. A careful reanalysis in 2000 of data collected by Seebohm Rowntree in York showed a dramatic fall in poverty rates between 1936 and 1950.[4]

These arrangements unravelled in the 1970s. Governments of both stripes saw trade union power as a threat not only to employers and their profits but also to wider democracy. The consequence was that government priorities favoured capitalists rather than the population as a whole. [5] The twin policies of full employment and universal social security were abandoned in favour of the control of inflation and economic growth – a conclusion made starker by the oil crisis and its repercussions. From 1977 onwards, the Gini coefficient, a single measure of inequality in society, began its inexorable rise.

Notwithstanding this changed direction, looking back over the 75 years since the Second World War, for much of this period widespread destitution – characteristic of Victorian times – was largely confined to marginalised groups such as homeless people, migrants and Roma. However, recently the problem of destitution has begun to return and, according to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, it was doing so before the pandemic.[6]

A sticking point

Even though we no longer see the widespread destitution of the Victorian era, high rates of poverty have always been with us. We have never managed to raise the incomes of the bottom quintile of society so that they can take full part in society.

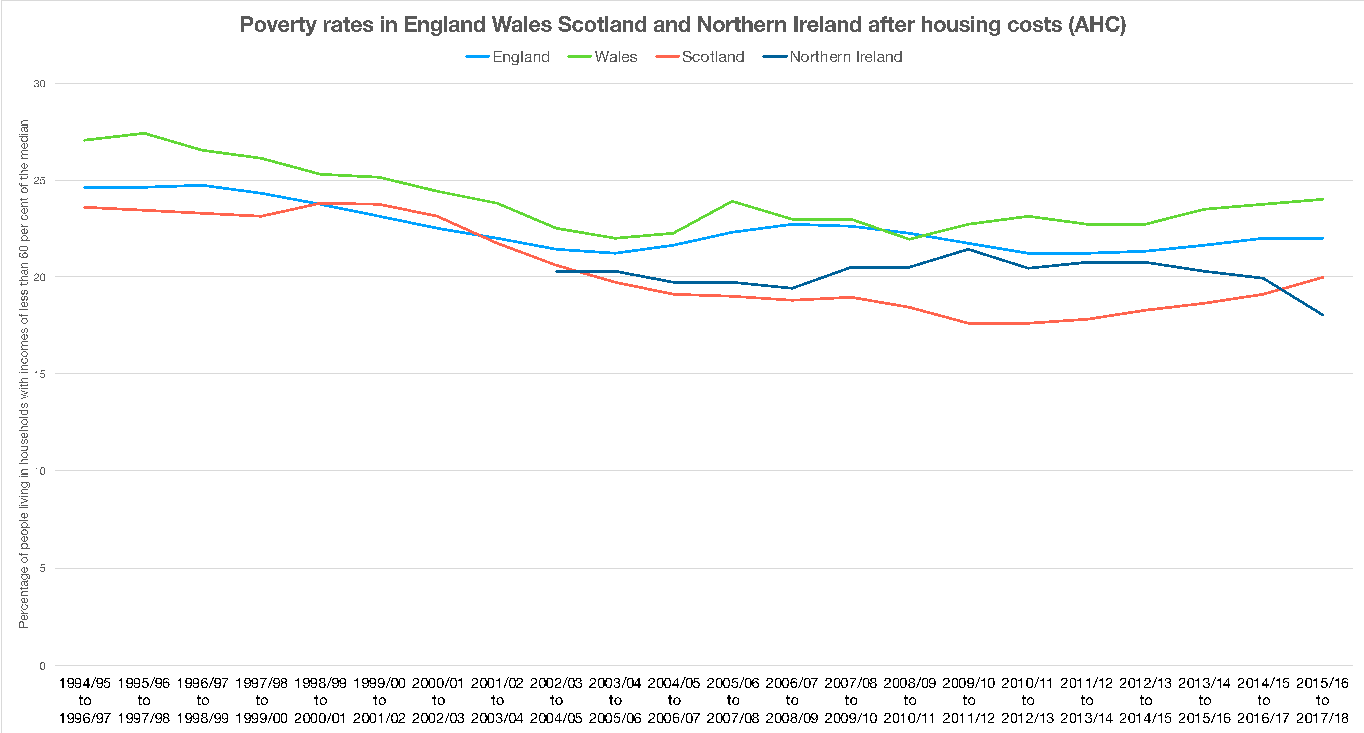

The following chart shows the official poverty rates in the four countries of the UK over the past 25 years.[7]

As can be seen, rates hover around the 20 per cent mark. The UK is not alone in failing to end poverty and much of the rest of Europe faces similar problems.[8]

A limited commitment

The persistence of poverty comes down to two main factors: political will and public attitudes. Governments have typically been lukewarm about addressing poverty and the public have never been much concerned.

The welfare state was weakened at birth by the wartime Beveridge committee’s decisions to set benefit levels below what was adequate for social inclusion, and income tax thresholds have long been determined by considerations of political economy rather than the alleviation of poverty.[9] The neglect of poverty has been an easy political choice because public opinion has never much favoured anti-poverty policies, and support for them has declined markedly since the 1960s.[10] Indeed, when he spoke at the centenary celebrations of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation in 2004, Gordon Brown, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, asked charities to do more to educate the public because hostile public attitudes limited the extent to which he could promote policies to reduce poverty.[11]

New promise

Gordon Brown’s attitude signified a welcome break with the past. In 1999, the Labour government promised to end child poverty by 2020. The Government set clear national targets. For example, the Treasury Child Poverty Review (2004) set a target to halve the number of children in relative low-income households between 1998-99 and 2010-11. This was a milestone on the way to eradicating child poverty by 2020.

As well as the income poverty headline targets, other targets were set for health, employment, education, social care and transport to chime with the child poverty and social inclusion agenda.

Government policy was comprehensive. It covered almost every sphere of life, including housing, financial inclusion, health, transport, education, parenting and many other things. Tackling child poverty was designed as a cross-government effort. While the child poverty target was owned by HM Treasury and the Department for Work and Pensions, it was clear that several other departments had major contributions to make. Following the publication of Every Child Matters in 2003, children’s services were brought together under a new Minister for Children and Families. These changes were designed to support more joined-up policy development and delivery for early years services, education, parenting support and wider children’s services.

The comprehensiveness of the policy notwithstanding, in practice there were two main strands. The first was to get people into work. Work was regarded as a sustainable strategy, because it creates income and reduces welfare dependency. The main efforts focused on people from workless households, lone parents, disabled people, and people from black and minority ethnic communities. Such efforts were supported by tax credits and the provision of childcare, so that work brought greater income than the value of the pay.

A second strand was Every Child Matters. This Green Paper highlighted the government’s aim of putting support for parents and carers at the heart of its approach to improving outcomes for children, and its wish to create more and better universal services and targeted services open to families as and when they need them. The government’s vision was for all parents to have access to parenting support in the form of information and advice, with signposting to more targeted and appropriate specialist support for those groups with more specific needs (such as disabled parents or parents with mental health problems). This approach was targeted on the social aspects of child poverty.

In 2008, the government brought these two strands together in Ending Child Poverty: Everybody’s Business.[12] A Joint Child Poverty Unit was set up to bring government departments together to provide an integrated approach, learn lessons, and formulate new initiatives.[13]

False hope

Despite early gains, government programmes faced diminishing marginal returns, and from 2005 onwards progress stalled.

A fatal weakness was the failure to convince the public that anti-poverty policies mattered, and their policies were easily undone when the Coalition Government came into power in 2010. Trading on the widespread hostility towards people labelled as ‘benefit scroungers’, the new government introduced austerity policies that reduced social security benefits. Cuts to public services over many years have meant that organisations such as local authorities have no spare capacity to think creatively about the problem, and even if they could, they do not have the necessary resources to do anything but help to stem the tide.

The pandemic and #BuildBackBetter

The consequences of the pandemic are yet to be felt fully because it is still with us. The Child Poverty Action Group has documented the consequences for families of the rise in unemployment and increased reliance on benefits. In a special survey, they found that:

‘As a result of the pandemic, nearly six in 10 families said they are struggling to cover the cost of three or more basic essentials, including food, utilities, rent, travel or child-related costs. Around half of all families said they have a new or worse debt problem.’ [14]

It is clear that the pandemic has created a huge problem for British society and there is widespread agreement that the effects will be most pronounced in places where poverty was high to start with.

The scale of the crisis is leading many to consider the prospect of developing a new society from the ashes of the old – to #BuildBackBetter.[15] The size of the task will probably resemble the scale of reconstruction needed following the Second World War and would benefit from a meeting like the Bretton Woods conference that planned for the peace in 1944.

Part 2: What now?

Finding hope

In two articles published in 2020, #BuildBackBetter and Facing the Shadow to #BuildBackBetter, I set out how the pandemic might open up new possibilities for a more compassionate world in which people’s new understanding of their vulnerabilities would lead to a greater sense of solidarity, and in turn to greater justice. How can we develop such a world in which we see that our fortunes are bound up in our relationships with one another and we put aside our differences to create a new operating plan for our society?

As things stand, it is unlikely that the radical changes necessary to build a society based on the principle of flourishing lives for all will emerge from Westminster. For example, none of the election manifestos for the 2019 election contained credible proposals to make a significant impact on poverty.

A new approach is needed, yet the broken nature of our national politics is unlikely to deliver it. As Hugh Ellis of TCPA says in a recent podcast, if we want progressive social change, we must look to civil society to deliver it because that is the source of creativity. ‘If we open our eyes to what is happening in our communities, we can find pathways to hope because they are all around us.’

We need multiple perspectives

Over the past three years, the Rethinking Poverty discussion hub has provided a forum for capturing some of this creativity. The variety of contributions shows that there is no monopoly of good ideas. Many people and organisations are in this space striving for a good society, which the Joseph Rowntree Foundation set out in its 2016 plan to solve poverty: ‘The UK should be a country where, no matter where people live, everyone has the chance of a decent and secure life.’

In its 2016 publication, Secure and Free, Compass produced an identical vision, developing ideas from organisations as diverse as Bright Blue, the Centre for Social Justice, Civitas, the Fabian Society, Friends of the Earth and The Good Right, together with individual commentators ranging from James Kirkup to Polly Toynbee.

Many different people from many different organisations are striving to implement such ideas. In the June 2021 edition of Prospect, for example, the Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby calls for ‘a new plan to remodel the exhausted and unequal society exposed by the virus’.[16]

We need an inclusive approach

If such ideas are to gain traction, we must recognise that no single person, no single organisation and no single idea will deliver a credible plan for a good society. We need a configuration of people and organisations to deal with the complexity of issues before us. We need to join together matters of the economy, the environment, and society in ways that offer a new way of deciding and doing what really matters to people.

A network of different approaches taken by different people and organisations, each connecting with each other through a central thread, is necessary to address complex problems which contain multiple interacting factors that cannot be individually distinguished. This means that any intervention addresses entire systems, rather than taking a piecemeal approach. Results can never be fully predicted because small inputs may result in disproportionate effects. Problems cannot be solved once and for ever, but must be systematically managed, since any intervention may give rise to new problems. Such systems cannot be controlled – the best one can do is to influence them, or, in the words of Donella Meadows, lead author of the classic study of systems theory Limits to Growth, learn to ‘dance with them’.

Sue Goss suggests that we need to adopt a Garden Mind. Rather than treating the world as if it is a machine, with inputs and outputs adding value, we should use an organic approach that draws on different resources and sources of power, celebrating diversity, experimenting, testing, sharing learning, and building strength through connectedness.

This approach means that we cannot treat the process of building a new society as a problem-solving exercise in which government rolls out a programme of work that delivers specific objectives. We must instead see it as a process that involves a new way of seeing, requiring a leap in moral imagination that cascades through participants and filters through to social attitudes in society.

If we are to make progress and to accommodate the diversity of people and views needed to build a good society, we need to abolish egos, logos, silos and halos. Binary logic – as in ‘I am right and you are wrong’– is an enemy of inclusion. We are all too ready to create enemies of people who share similar perspectives yet differ on details. We should beware such hostilities. James Scurry in The Great Slowdown quotes poet Henry Wadworth Longfellow:

‘If we could read the secret history of our enemies, we should find in each man’s life sorrow and suffering enough to disarm all hostility.’[17]

A new kind of dialogue

We need to find ways of talking to each other differently. This involves true dialogue starting from a place where everyone is humble, putting aside ego and engaging in exploration together. In his last book, On Dialogue, physicist David Bohm explored the original Greek meaning of dialogue and suggested that the object of a dialogue is not to analyse things, or to win an argument, or to exchange opinions. Rather, it is to suspend your opinions and listen to everyone else’s, and to see what all that means. This will make possible a flow of meaning in the whole group, out of which may emerge some new understanding. This may not have been in the starting point at all. And this shared meaning is the ‘glue’ that holds people and societies together. The key word here is ‘solidarity’ – another concept that came to prominence during the pandemic as people in communities have stepped forward to help each other.

The pandemic has stimulated these kinds of conversations. One of these,

We Contain Multitudes, is a shared space for people who wish to:

Speak softly

Listen deeply

Seek a better world

Knowing that we contain multitudes

We are one world with many peoples

One people with many worlds.

Diversity is a wonderful strength when combined with unity. Let us admit past disassociations and mistakes, be less judgemental, and bring compassion to our conversations.

Such characteristics were present in a conversation called Anger Atonement and Healing between Oxford academic Simukai Chigudu, an activist in the ‘Rhodes must fall’ campaign, and Albie Sachs, chief architect of the South African constitution, who was largely responsible for the creation of the Constitutional Court Complex that was built on the site of three notorious prisons in Johannesburg, which now stands as one of the world’s foremost examples of a suite of acknowledgement, commemoration and atonement..

In Colonialism had never really ended: my life in the shadow of Cecil Rhodes, Chigudu describes horrible racist experiences he faced as a boy when coming from Zimbabwe to the UK to study at Stonyhurst school, and which continue to this day. In the context of Black Lives Matter and its efforts to address the structural racism that pervades our world, the two differed on how to address statues that symbolise the oppression of our colonialist past. Their conversation was a wonderful example of how to discuss difficult questions, acknowledge pernicious racism, and yet avoid the false binaries of different cultural camps.

We have resources

If we desire a new world, it will have to be co-created from the bottom up using a multiplicity of perspectives and resources. And we have those resources. In Ruth Lister’s second edition of Poverty, for example, we have a comprehensive and enduring picture of how to begin to frame solutions within a positive vision of a good society.

We also have the wisdom of ages to draw on – for example the vision of the garden city movement, described above – and the experience of activists, such as those involved in campaigns to #ShiftThePower or campaigns for a Living Wage. Environmental campaigns are particularly vibrant. There are currently 419 entries on the National Grassroots Campaigns Map. As March’s Talking Points noted, co-founder Rosie Pearson was astonished by its popularity: ‘When we set it up, it was really just to see what’s out there. But we quickly realised there’s a real hunger for sharing information, resources and support.’ At local level, we are seeing an outburst of creativity. A key task is to join up the actors seeking different pathways to a good society where everyone can flourish. In developing a new system, often all we need to do is to scale up activities that are already present. As Neal Lawson puts it in 45° Change:

‘To ensure humanity and the planet benefit from today’s technological transformation, the state is going to have to help join up, scale up, accelerate, replicate and project emerging forms of collaborative action to ensure they become the predominant form of “deciding and doing” in the 21st century.’

This is a task requiring co-creation, so that whatever emerges adds value to all people, rather than just small groups that benefit disproportionately from private economic growth.

Influencing power holders

At some point, the creativity emerging from civil society needs to influence how the state operates. As the pandemic has shown, state intervention is the only way that serious resources can be mobilised.

Rather than muddling along, as governments are apt to do, we need a ten-year plan with wellbeing as its goal. Wellbeing means that people feel good, have robust physical and mental health, and find fulfilment in their work, leisure and family lives. The Carnegie UK Trust has developed a framework for how to develop wellbeing in society.

Changing our values

Such a plan needs to address the culture of individualism that has prevented us solving the problem of poverty.

Despite much rhetoric about how the pandemic has brought us all together and fostered a ‘blitz spirit’ of helping one another, underlying social attitudes to people in poverty have not changed much. Unequal Britain: Attitudes to Inequalities after Covid shows that Britons’ focus on hard work and ambition means they tend to have a relatively unforgiving view of those who have lost their jobs during the crisis. These attitudes are unhelpful if we wish to build a society based on solidarity because they hark back to the notion of the deserving and undeserving poor.

We saw a rebirth of this paradigm as neoliberalism emerged in the 1970s. The emphasis on the market forged a new set of social attitudes that undermined the collective vision of Joseph Rowntree and Beatrice Webb at the dawn of the 20th century. Two years after her 1979 victory, Margaret Thatcher gave an interview to the Sunday Times in which she said: ‘Economics are the method: the object is to change the soul.’ The consequence was, according to historian Selina Todd: ‘Generations who had grown up in the individualistic 1980s and 1990s were even more convinced that they were responsible for their circumstances … By 2010, people were less likely to see class and inequality as a means of making sense of their circumstances.’[18]

Mindset matters. Unless we can begin to apply the principle of Ubuntu in our lives – I am because you are – it is unlikely that we have much of a future. Without a big shift, we will sleepwalk into the coming environmental crisis, just as we did into the pandemic. It is time for an awakening.

How do we build trust?

Central to such an awakening is a process to build trust within society. Without such a foundation of trust, policies, programmes and practices will fail to deliver what we need to flourish in the 21st century because only compassionate processes will lead to worthwhile outcomes. My next article will set out how I envisage we might approach this together.

[1] Hugh Ellis (2021) ‘The spirit of ’47’, Town and Country Planning, May/June, pp 143-4.

[2] The draft of Joseph Rowntree’s memorandum can be found at https://www.rowntreesociety.org.uk/currentprojects/rowntree-a-z/joseph-rowntrees-1904-memorandum/

[3] D Coates (2012) From the Poor Law to Welfare to Work: What we have learned from a century of anti-poverty policies,London: Smith Institute and the Webb Memorial Trust.

[4] T Hatton and R Bailey (2000) ‘Seebohm Rowntree and the post-war poverty puzzle’, Economic History Review 53(3): 517–43.

[5] Selina Todd (2014) The people: the rise and fall of the working class, 1910-2010, London: John Murray, p 314.

[6] https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/destitution-uk-2020

[7] Based on living in a household with less than 60 per cent of the median income. Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/households-below-average-income-hbai–2

[8] For up-to-date European data, see https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/pdfscache/29306.pdf

[9] https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/jun/03/john-veit-wilson-obituary

[10] https://www.rethinkingpoverty.org.uk/events/uk-poverty-and-inequality-workshop-report/

[11] G Brown (2004) ‘Our Children are our future’, Speech at Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 8 July.

[12] HM Treasury, Department of Work and Pensions, and Department for Children, Schools and Families (2008), Ending Child Poverty: Everybody’s Business.

[13]Beverley Hughes (2008) ‘Invitation to submit expressions of interest in local authority led pilots to tackle child poverty’, email to Chief Executives and Directors of Children’s Services, 24 July.

[14] https://cpag.org.uk/policy-and-campaigns/report/poverty-pandemic-update-impact-coronavirus-low-income-families-and

[15] https://www.rethinkingpoverty.org.uk/rethinking-poverty/building-back-better/

[16] Justin Welby (2021) ‘How to build a new Beveridge’, Prospect, June, p 37-9.

[17] J. Scurry (2021) The great slowdown, Compass, at press

[18] Todd op.cit., p 356

Barry Knight is Secretary to Centris Trustees, a member of PSJP’s Management Committee, a regular contributor to Rethinking Poverty, and Adviser to the Global Fund for Community Foundations.

This post was first published by Rethinking Poverty.