To follow up his article, #BuildBackBetter, Barry Knight is researching practical ways to make this happen. In the first of a series of articles, he examines the role of the individual, and concludes that a necessary condition of rebuilding society is to face the ‘shadow’ we all have within ourselves.

The air is thick with chickens coming home to roost. Problems we have ignored for too long are landing one by one – first the pandemic, second the economic collapse and third the race crisis. Next, we will feel the full force of the climate emergency.

We humans are not built to deal with such rapid change. Half a century ago, Alvin Toffler coined the phrase ‘future shock’, which he defined as ‘too much change in too short a period of time’.(1) It’s as if we’ve been living in a kaleidoscope. No sooner does one chicken land, then another, and then another.

It is small wonder that people feel out-of-sorts. Having talked in depth with around 100 people over the past three months, almost everyone expresses an underlying sense of unease, feeling oddly disconnected and searching for something that makes sense. In, #BuildBackBetter, written at the beginning of the lockdown, I suggested that this was due to having entered the limen – an ambiguous zone of radical change destroying our frameworks, causing feelings of panic, fear, loss and confusion, and yet with no clear light at the end of the tunnel.

While such confusion may be uncomfortable, it may also presage a new world. The lockdown has given people an opportunity to consider things we don’t normally talk about – who we are in the world, how we construct meaning, and what we can draw from our current crises and predicaments to find a new future that resonates more with us as human beings living in a natural ecosystem, rather than as machines in service to an economy that has come to diminish our humanity.

How can we avoid going back to the pre-crisis world?

At the beginning of the lockdown, French philosopher and anthropologist Bruno Latour asked: ‘What protective measures can you think of so we don’t go back to the pre-crisis production model?’ In a recent interview, he was asked why this exercise resonated all over the world. He replied:

‘Even if you were not a spiritual person, the lockdown forced everyone into a kind of retreat, a moment for reflection. It was quite extraordinary. The questions were therapeutic. They gave people powerlessly stuck at home a way of thinking about how they would create a better future.’

The desire for a new world is shown in the spread of the #BuildBackBetter hashtag, which has achieved exponential popularity, becoming a meme for many different people and organisations who see the crisis as offering new possibilities for humanity if we can seize the moment.

It also shows that change can and does happen very fast. As Latour explains:

‘Covid has given us a model of contamination. It has shown how quickly something can become global just by going from one mouth to another. That’s an incredible demonstration of network theory … It shows that we must not think of the personal and the collective as two distinct levels. The big climate questions can make individuals feel small and impotent. But the virus gives us a lesson. If you spread from one mouth to another, you can viralise the world very fast.’

This is exciting, and suggests that we could have a new and better world soon – in line with Malcolm Gladwell’s ‘tipping point’. The fact that Compass has developed a range of themes to #BuildBackBetter and to galvanise more than 350 organisations to support a series of policy recommendations is highly encouraging.

The dangers of false certainty

At the same time, as the hashtag has become a meme, and spread widely into all sorts of unlikely places, there are dangers. While memes can be thought of as cognitive versions of viruses, carrying cultural ideas, symbols or practices transmitted from one mind to another, their lack of specific and fully formed normative content means that they are open to a variety of interpretations and can therefore be misused. To put this another way, the #BuildBackBetter meme has hitched itself to all sorts of partly formed propositions that bear no relation to one another nor any connection with a coherent theme that will enable us to find a way through the mess that we find ourselves in. For some, this is a kind of land grab– a way of legitimising a pre-existing point of view of the world. Views are being put forward as if they are certain to solve our problems, yet the truth is that they are mostly untested.

Such false certainty is an enemy. As a saying often attributed to Mark Twain puts it:

‘It ain’t what you know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.’

False certainty is breeding an atmosphere of intolerance of other opinions that is driving a culture of hate in public discourse. We would do well to remember that certainty is a quality beyond the reach of human beings. Commenting on the uncertainty principle in physics, biologist J B S Haldane noted:

‘Now my own suspicion is that the Universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose.’(2)

Turning from science to poetry, Robert Graves speaks to such uncertainty in his In Broken Images. The final two stanzas are:

‘He continues quick and dull in his clear images;

I continue slow and sharp in my broken images.

He in a new confusion of his understanding;

I in a new understanding of my confusion.’

Facing the pain of problems

Rushing to the wrong conclusion will do more harm than good. In contemplating the necessary changes in our psyche, we need time. We must go deeper, perhaps facing the secular equivalent of the ‘dark night of the soul’ to change our mental models. In The Road Less Travelled, Scott Peck draws on his work as a psychiatrist to show that facing the pain of problems is the only authentic way of finding meaning in life, yet most people avoid this pain. The book shows that there are techniques of suffering that enable the pain of problems to be worked through and systematically solved. Without facing what we need to, we live in a superficial and meaningless world, allowing problems to grow beneath our feet without realising it. And then, the chickens come home to roost.

As Donella Meadows, lead author of Limits to Growth, pointed out half a century ago, deep change depends on new ways of seeing. To intervene effectively in a system, the most difficult and ultimately most effective point of intervention is to shift the mindsets and paradigms that underlie behaviour. These are the most deeply held beliefs that drive a system or were used to design it.

The systems iceberg

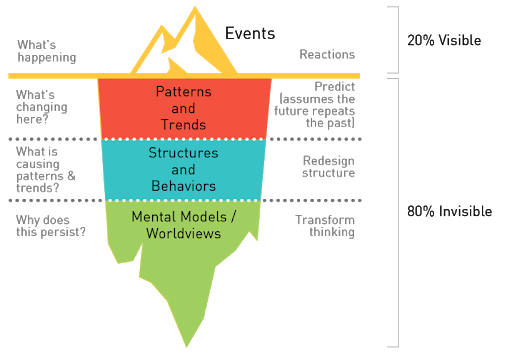

To get at the roots of problems, systems theory uses the ‘systems iceberg’. First developed by Edward T Hall in 1976, this looks at how various elements within a system – which could be an ecosystem, an organisation, or something more dispersed such as a supply chain – influence one another.(3) Rather than reacting to individual problems that arise, a systems thinker will investigate relationships between activities within the system, look for patterns over time, and identify root causes.

The iceberg is a useful metaphor because it has only 10 per cent of its total mass above the water while 90 per cent is underwater. But that 90 per cent is what the ocean currents act on, and what creates the iceberg’s behaviour at its tip. Global issues can be viewed in the same way.

The iceberg model typically has four categories. Above the waterline are ‘events’. Here, to take an example from the field of poverty, a recent event is a news item reporting an 81 per cent increase for emergency food parcels from food banks during the last two weeks of March 2020. The next level down is ‘patterns and trends’. Looking below the surface, we find an exponential rise in the use of food banks over the past ten years. Further down, we find ‘structures and behaviours’, and see that austerity regimes began in 2010 and Universal Credit was introduced during this period. At the bottom, we find mental models and worldviews. At this level, we find widespread hostility towards people in receipt of social security payments and a view that people in poverty have made bad choices that mean the state should not look after them.

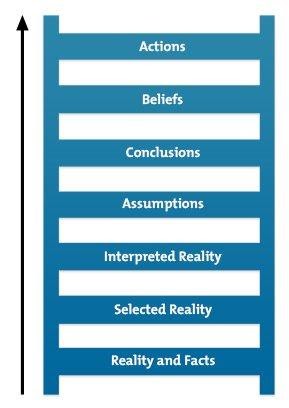

What lies at the bottom of the systems iceberg is of critical importance to what happens in the system. This is because of what cognitive scientists call the ladder of inference: the way that mental models affect the way that we take decisions about action in the world.

Starting at the bottom of the ladder, we have reality and facts. From there, we:

- Experience these selectively based on our beliefs and prior experience

- Interpret what they mean

- Apply our existing assumptions, sometimes without considering them

- Draw conclusions based on the interpreted facts and our assumptions

- Develop beliefs based on these conclusions

- Take actions that seem ‘right’ because they are based on what we believe

This can create a vicious circle. Our beliefs have a big effect on how we select from reality, and can lead us to ignore the facts altogether. Soon we are literally jumping to conclusions – by missing facts and skipping steps in the reasoning process. In his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman summarises decades of research conducted with Amos Tversky that demonstrates the systematic biases and errors in the way that humans think.

The limited utility of rationality

Rationality has limited utility in public life because people are not rational. It is what lies deep in our psyche that matters. Conservative politicians have understood this very well. Two years after her 1979 victory, Margaret Thatcher gave an interview to the Sunday Times in which she said:

‘Economics are the method: the object is to change the soul.’

Contrast this with the behaviour of Labour governments’ policies towards poverty between 1997 and 2010. In Decent Childhoods, which reviews Labour’s performance, Kate Bell and Jason Strelitz showed that Labour’s anti-poverty politics had been introduced by stealth and had done little to engage the public, so were easily reversed when Labour lost power. As Selina Todd showed in her history of the working class, generations who had grown up in the 1980s and 1990s had absorbed the neoliberal ethic that people are responsible for their circumstances.(4) It is pointless to develop policies and programmes in a society that run counter to the underlying values and culture of that society and expect them to stick.

During a recent Ariadne webinar, Naomi Klein described the failure of progressive thinking following the 2008 financial crisis:

‘Neoliberalism has polluted our imagination, made collective action suspect.’

While our underlying mindset is based on a philosophy that pays scant attention to human needs, policies and practices that are already in the Overton Window are most unlikely to meet the needs of a new and more humane world.

A new moral imagination

As John Paul Lederach says, we need a new moral imagination:

‘The wellspring lies in our moral imagination, which I will define as the capacity to imagine something rooted in the challenges of the real world yet capable of giving birth to that which does not yet exist.’

Ratiocination – the use of logic and evidence – is of little use here. We need to enter the realm of creativity and wonder. As my friend Colin Greer puts it, poetry helps because it ‘pushes us to the edge of words and beyond the limits of boundaries’. In response to an early draft of #BuildBackBetter, he sent me the draft of a poem subsequently published as Build Better:

Hymn to the rhythms of Chariots of Fire

Refrain:

Give me your soul

In gratitude

Tear up your scarlet letter

Share your soul

In certitude

We can build better.

No more chanteuses washed up in storms

No babies burned in fires

No home a mere haven from disease

But a boundary on desire.

No more caged hummingbirds

Flying north to mate with flowers

No distended skin and bone

Served up for ginger givers.

No rebuilding of the past

No loose tile in the rafters

No hard boiled eggs atop of walls

No cost saving disasters.

No greed to weaken hardened steel

Fired up to build bridges

No interest rates that maim and kill

But souls grown bold enough to kneel

And build better…

Refrain:

Give me your soul

In gratitude

Tear up your scarlet letter

Share your soul

In certitude

We can build better.

For me, this poem takes us straight into what we need to do. It takes us into ‘soul work’. We need to go deep into the collective unconscious and transform ourselves. This is not an airy-fairy process, but involves intense work of self-examination proposed by serious writers including Carl Jung, Alice Miller, Roberto Assagioli, James Hillman, Robert Bly, Robert A Johnson, Alan Watts and others.

Addressing the shadow

The key to such work is to address ‘the shadow’. This is that part of our personality that is incompatible with our chosen conscious attitude about ourselves. Every young child knows kindness, love and generosity, but children also quickly learn anger, selfishness and greed.

These emotions are part of our shared experience. But as we grow up, traits associated with ‘being good’ are accepted, while others associated with ‘being bad’ are rejected. As poet Robert Bly says in A Little Book of the Human Shadow, children are taught to put all of these unwanted parts into an invisible bag and drag it behind them.

This rejected side becomes the shadow, the ‘dark side’ of our personality, because it consists chiefly of primitive, negative emotions and impulses like rage, envy, greed, selfishness, desire, and the striving for power.

Not all shadow characteristics are negative but whatever we perceive as inferior, evil or unacceptable becomes part of the shadow. In patriarchal societies, men may split off qualities such as compassion, vulnerability and empathy. For example, bell hooks points out that:

‘… patriarchy demands from all males that they engage in acts of self-mutilation, that they kill off the emotional parts of themselves. If an individual is not successful in crippling himself, he can count on patriarchal men to enact rituals of power that will assault his self-esteem.’

I know this from personal experience. When I was young, a favourite uncle had a bad stroke, and it seemed he would die. On hearing the news, I burst into tears. My father reprimanded me sharply and told me to pull myself together. In that moment, I felt like a tree being felled by an axe. Over time, I repressed my emotional side and became a hard-edged, analytical person. It took me years of soul work to recover my shadow and begin to feel again. Despite loving my father, I did not cry when he died and could not do so in the 30 years since – that is, until I wrote this sentence when, finally, in a huge and welcome release, the tears welled up inside me and poured down my face as the shadow found the light.

Redemption at last! We can’t defeat the shadow, but instead have to face it and incorporate it into our personality. That way, we become whole and retrieve the parts we have split off through repression.

Projecting the shadow on to others

Retrieving the shadow is difficult because it becomes part of our unconscious so that we fail to see it. We invariably project the parts we disown within ourselves on to other people, objects, and the environment. Projection and shadow go hand in hand. When someone evokes an emotional charge in you, it’s a sign that you’re projecting a disowned quality from your shadow on to this individual. This is Anna Freud’s mechanism of ego defence that lies at the heart of stereotyping and scapegoating others, since we project on to others a characteristic that we have disowned in ourselves. In research for Rethinking Poverty, we observed that people who are on the edge of poverty are more likely than others to demean people living on social security benefits as ‘scroungers’. As psychotherapist Alice Miller puts it in The Drama of the Gifted Child:

‘Disregard for those who are smaller and weaker is … the best defence against a breakthrough of one’s own feelings of helplessness …’(5)

Ontological insecurity breeds the projection of hate.

Carl Jung, who made extensive use of the shadow in his work, argued that scapegoating at a collective level has dangerous consequences for society. Those unwilling, or unable, to face up to their shadows are easy prey for collectivist movements which have ready-made scapegoats in the form of political opponents, members of different ethnic groups or socioeconomic classes. Scapegoating at the level of collectives, in other words projecting our problems on to groups of people who differ from us, proves attractive for several reasons. It allows us to avoid the damage to our personal relationships which occurs when we use someone close to us as a scapegoat. Furthermore, given that our interactions with members of the scapegoated group are usually limited, we do not risk awakening to the realisation that these people are not nearly like the distorted image of them we hold in our psyche.

Many of the world’s leaders are in the grip of their shadow and project it on to groups and countries that they see as enemies. In a recent Washington Post article I’ve seen dictators rise and fall, Salman Rushdie notes common characteristics of dictators:

‘Extreme narcissism, detachment from reality, a fondness for sycophants and a distrust of truth-tellers, an obsession with how one is publicly portrayed, a hatred of journalists and the temperament of an out-of-control bulldozer …’

Such characteristics, displaying the basest impulses of the collective shadow, produce greed, hatred and violence – which, when combined with command over weapons of mass destruction, threaten the entire world.

How to deal with this?

How do we deal with this? The issues are so big and all-encompassing that we can only feel overwhelmed.

While I don’t know – and can’t know – the answer, I have an inkling that opposing hatred head-on with hatred makes things worse. History suggests that when anger and hate is met with anger and hate, it produces even more anger and hate. Twitter spats, angry exchanges in Parliament, and tit-for-tat killings in violent conflicts all feed the cycle. In binary conflicts, the shadow projected from one side feeds the shadow projected from the other side. It just gets darker and darker.

Somehow, we must break this cycle of a binary world. Again, we don’t know how, but a starting point is to recognise that we can’t change the behaviour of the ‘other’, but we can change the behaviour of the self. If we can substitute the amalgam of anger and hate within ourselves to an amalgam of love and power, we may be able to transform ourselves and use a different kind of energy in the world.

Fusing power and love

This sentiment draws on the ‘beloved community’ identified by the civil rights movement 60 years ago in which two seeming antinomies – power and love – are fused together. As Martin Luther King (1967) put it:

‘What is needed is a realization that power without love is reckless and abusive, and that love without power is sentimental and anemic.’

What does this look like in practice? An example is Oscar Peterson’s Hymn to Freedom. This was written as a response to the violence against African Americans in Birmingham, Alabama (known at the time as ‘Bombingham’) in the early 1960s. The music is full of grace, reverence and symmetrical beauty, but also steel and determination. These qualities explain why the music became a symbol of civil rights and remains a potent symbol for those who want to see a just world.

The combination of love and power is not something a think-tank can deliver. There is no policy prescription that can be launched or set out in a press release. Such preachy stuff will fail because it will find itself at the bottom of the ladder of inference and have little prospect of getting beyond the first rung.

Modelling a new way of being

We must model a new way of being that is present in each and every action in the moment. It is an approach to relationships that fits with the feminist approaches of Mary Parker Follett and Jean Baker Miller, both of whom went deep into the nuances of power. I wrote about this in #BuildBackBetter but formulated the argument wrongly. I suggested the need for ‘power sharing’, but Linda Guinee pointed out:

‘Power sharing assumes that power is a fixed quantity that can be divided, where power building assumes you can support groups to build power – not a fixed sum thing – and done in relationship.’

This goes to the heart of the matter. If power is part of a zero sum game in which ‘either I have the power or you do’, this takes us straight into the binary world we are trying to escape. If, on the other hand, power is a relational quality that we build together, power is potentially infinite – so long as we treat each other as assets and support each other to get more.

Such a perspective shifts the nature of human interaction. In his last book, On Dialogue, the physicist David Bohm showed how conversations, discussions, dialogue and respectful debate can produce agreements about the fundamentals of what it is to be human. Through an extended process we can find ‘tacit knowledge’ – the underlying principles of what it means to be a fair-minded, caring, fully grown human being who engages with his or her peers with a set of common understandings of what it means to be alive and what each of us wants and needs. A key question is: how can I become me while helping you to become you?

Creating long-term visions for the future

In answering such a question, while acknowledging the existence of our short-term needs and interests, we put aside our egos and silos and share long-term visions for our children and grandchildren. We think of the broader field that humanity inhabits alongside other fauna and flora. We are kind and caring and see the love in all things. We go beyond the trance of separation to see that we are all connected and part of a universe that depends on us being respectful towards all things. Such a perspective fits with David Bohm’s groundbreaking work in physics described in Wholeness and the Implicate Order.

Such a perspective gives us a new model of the ego. We are not a separate force in the world but an influence on a wide range of relationships. This means greater humility in how we approach our own views, needs and interests, seeing ourselves as part of a collective way of being and acting.

Such humility is one of the lessons of what many people regard as the most prescient novel for our times – The Plague by Albert Camus, published in 1947. Set in Oran in 1941, the story tells the story of a year-long epidemic that kills one-quarter of people in the town. The essential meaning of the book is that the plague may recede, but it will come back. Our trappings of careers, fancy restaurants, foreign holidays and ever more wealth will not save us. The question for the human condition is how to find meaning in the context of such absurdity.

The plague forces us to re-evaluate life when we come face-to-face with the reality of ontological insecurity. Alan Watts shows how the system masks this, by proffering the myth that it can be overcome by commitment to a career. In a lecture called The Hoax, he says:

‘We thought of life by analogy with a journey, a pilgrimage which had a serious purpose at the end. Success, or maybe heaven after you’re dead. But we missed the point the whole way along. It was a musical thing and we were supposed to sing or dance while the music was being played.’

The illusion of a consumer society

Yet the systems we live in are hardwired into a notion of progress that means that we never have ‘enough’ and always need more. This breeds a sense of scarcity in ourselves and a consumer society that means that we have to invest in our futures, strive for achievement, make more money, find better jobs, shop more and get bigger houses if we are to fulfil ourselves. All this is illusion, and shackles us to a system of capitalism that drives what 13th century poet Rumi called ‘thieves of the heart’ – greed, ego, anger and insecurity. In the process, we destroy what really matters. As Neal Lawson puts it in All Consuming:

‘We are in danger of losing sight of what is important in life, like kindness, playfulness, generosity and friendship. The immaterial things that can’t be bought.’(6)

Society is obsessed with ‘having’ and too little with ‘being’. In constantly pursuing more – more of this and more of that – we have fallen foul of what Alan Watts called the law of reversed effort. In his 1951 book, The Wisdom of Insecurity, he says:

‘Whenever you try to stay on the surface of the water, you sink; but when you try to sink you float.’

Accepting that you are ‘enough’

Striving after more means that you sink because you can never reach the point of repose at which you are ‘enough’. Taking away the law of reversed effort means that we accept ourselves the way we are and see ourselves as an asset, as opposed to a deficit that needs something else in order to fulfil ourselves. Educationalist Ken Robinson has demonstrated time and time again how our education system is based on such a deficit model and in the process diminishes creativity by its requirements for conformity, compliance and standardisation. His presentation ‘Do schools kill creativity?’ is the most watched TED talk of all time, yet we still put children through Standard Assessment Tests (SATs) that cause anxiety in children while being aware of research that demonstrates that anxiety interferes with learning.

A system that operates this way creates winners and losers. Most people feel like failures because they are at the wrong end of an elite-driven, top-down society, with high rewards for those at the top and disregard for everyone else.(7) A study by Rosie Carter for Hope Not Hate has mapped the consequences of this approach, showing the geographic distribution of people with different social attitudes, which suggests deep divisions at the heart of society in the UK.(8) No amount of remedial public services, charitable action or other forms of ‘doing to’ can address the indignities that have been perpetrated in the name of ‘growth’ and ‘progress’.

A New Jerusalem moment

How do we create a society in which everyone wins? A first and essential step is to work on ourselves to downplay our ego, to tame the desire to conquer and win, to find ways of conveying dignity on all people, while treating our planet with the care and respect it deserves. Such a perspective requires us to think very differently from the way we have been doing. It will involve us dismantling the empires of power we have built in the name of doing good and creating open systems that include us all as equals in crafting new solutions.

This could be a ‘New Jerusalem’ moment. In 1985, Elizabeth Durbin wrote a book with that title(9) describing the efforts of a group of young economists working in the 1930s to find a way out of the economic turmoil of the period, which bore fruit in the post-1945 settlement. As I write this, I am aware that there are many efforts to reproduce these efforts for the current age.

While we desperately need new economic models and the search for them has been a recurring theme on the Rethinking Poverty discussion hub over the past two years, it is important that we do not conceive this as a technocratic exercise. If any model is to work, it has to engage the emotions of our collective psyche.

To do this, let us go back to Colin Greer’s poem ‘Build Better’. The rhythms are based, he says, on ‘a hymn to the rhythms of Chariots of Fire’. I take this to be a reference to the 1981 film about the 1924 Olympics, in which the hymn is derived from the poem by William Blake adapted and called Jerusalem with music written by Sir Hubert Parry.

The hymn has special significance in our history, uplifting spirits when it was first sung in 1916 during the gloom of the First World War, adopted by the Suffragettes, used as the campaign slogan for the Labour Party in 1945, and sung at Conservative and Liberal party conferences subsequently.

In the film Chariots of Fire, the symbolism of the song ‘Jerusalem’ – sung at the end of the film – is that the different conflicts and tensions have come together in such a way that everyone wins and the human spirit emerges victorious. The result is a sense of wholeness in individuals and a united community. Inner work on the soul and outer work on the society are interconnected, and we must bring them together at every stage in building a new society. The last stanza of the hymn puts it like this:

‘I will not cease from Mental Fight,

Nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand:

Till we have built Jerusalem,

In England’s green & pleasant Land.’

- A Toffler (1970) Future Shock, New York: Bantam Books

- J B S Haldane (1927) Possible Worlds and Other Essays, London: Chatto and Windus, p 286

- E T Hall (1976) Beyond Culture, Garden City, NY: Anchor Press

- S Todd (2014) The people: the rise and fall of the working class, 1910-2010, London: John Murray, p 356

- A Miller (1997) The Drama of the Gifted Child, 2nd edition, New York: Perennial, p 72

- N Lawson (2009) All Consuming, London: Penguin Books

- R Peston (2017) WTF?, London: Hodder & Stoughton

- R Carter (2018) Fear, hope and loss: Understanding the drivers of hope and hate, London: Hope Not Hate

- E Durbin (1985) New Jerusalems, London: Routledge

Barry Knight is Secretary to Centris Trustees, a member of PSJP’s Management Committee, a regular contributor to Rethinking Poverty, and Adviser to the Global Fund for Community Foundations.

This post was first published by Rethinking Poverty.