Looking at the history of poverty, there appears to be one certainty: poverty has been a feature of every human society since time immemorial. As the Bible says: ‘The poor you will always have with you’ (Matthew 26:11).

A breakthrough

In the 19th century, philanthropy worked hard to overcome this, and by 1909 there was a breakthrough. Launching her Minority Report of the Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and Relief of Distress 1905–09, Beatrice Webb said: ‘It is now possible to abolish destitution.’ [1] Her proposals relied on state action, rather than philanthropy, and involved a managed economy, guaranteed minimum incomes and reform of the structures that produce inequality.

Progress

Gradually, state action took hold. The Beveridge Report of 1942 aimed to end the five great evils of want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness. Post-war policies were designed to guarantee full employment and to provide social security for all citizens.

Looking back on the 75 years since the Second World War, much has been achieved. By the beginning of 2020, widespread destitution – characteristic of Victorian times – was largely confined to marginalised groups such as homeless people, migrants and Roma.

A sticking point

While widespread destitution has ended, widespread poverty remains. We have never managed to raise the incomes of the bottom quintile of society so that they can take full part in society.

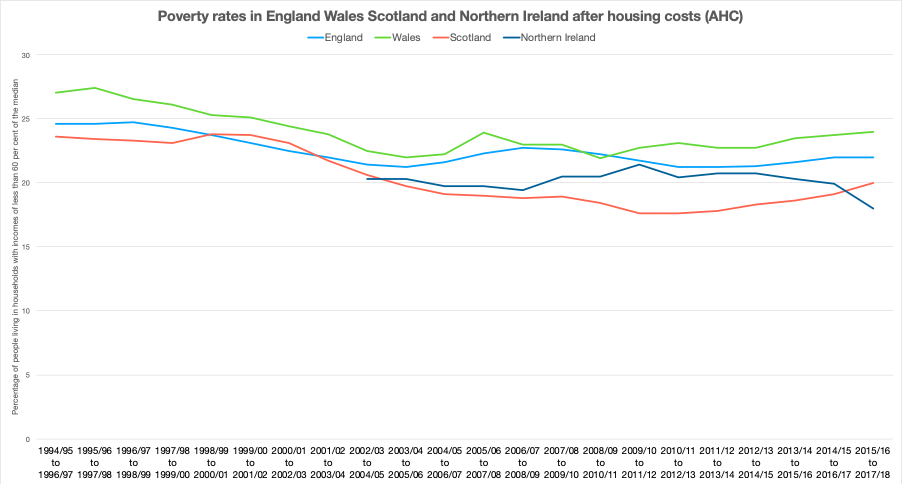

The following chart shows the rates of official poverty rates in the four countries of the UK over the past 25 years.[2]

As can be seen, rates hover around the 20 per cent mark. The UK is not alone in failing to end poverty and much of the rest of Europe faces similar problems.[3]

A stain on our society

Given the scale of our social, economic and technological advance, it is remarkable that we allow this continuing stain on our society. There is much evidence that poverty spoils lives, costs public money and destabilises social relations in a cycle that passes from one generation to the next. We may have done away with the humiliation of the 19th-century soup kitchen, but we are fast replacing it with the humiliation of the 21st-century foodbank.[4]

A limited commitment

The persistence of poverty comes down to two main factors: political will and public attitudes. Governments have typically been lukewarm about poverty and the public have never been much concerned. Government policies were weakened at birth by the wartime Beveridge committee’s decisions to set benefit levels below what was adequate for social inclusion, and income tax thresholds have long been determined by considerations of political economy rather than the alleviation of poverty.[5]

A welcome break with the past occurred in 1999, when the Labour government promised to end child poverty by 2020. Despite early gains, government programmes ran out of steam, and in 2005 progress stalled. A fatal weakness was the failure to convince the public that anti-poverty policies mattered, and their policies were easily undone when the Coalition Government came into power in 2010. Trading on the widespread hostility towards people labelled as ‘benefit scroungers,’ the new government introduced austerity policies that reduced social security benefits.

Rethinking Poverty

The failure to end poverty was the motivation for my book Rethinking Poverty. Based on a five-year study by the Webb Memorial Trust, it showed that the two traditional routes out of poverty – jobs and state benefits – were no longer working. Moreover, charities’ appeals for support for people in poverty were increasingly falling on deaf ears, and the framing of the debate by the poverty lobby was merely preaching to the converted.

The book concluded that progress could be made only by following a principle articulated by Buckminster Fuller:

‘You never change something by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.’

The Rethinking Poverty discussion hub is designed to develop a narrative for this new model society.

The crises

The tsunami of crises – health, economy and race – has accentuated the need for a new model. Evidence suggests that poverty has already risen dramatically and we could be soon in a world where destitution is the norm.

Local Trust has produced Our COVID Future, which consists of four possible scenarios. In one of the scenarios – the rise of the oligarchs – the dark phoenix emerging from the ashes of COVID-19 is a government of the few: polarised, xenophobic, and corrupt. We could well see a world in which a few giant companies rule the roost aided and abetted by despotic rulers more interested in their own narcissism than the public good. Closing space may close, and we may see a planet where most people are slaves to the gig economy. To avoid this, we need to #BuildBackBetter.

#BuildBackBetter

In #BuildBackBetter, written at the beginning of the lockdown, I suggested that humanity had entered the ‘limen’ – an ambiguous zone destroying our frameworks, causing feelings of panic, fear, loss and confusion, while nevertheless holding out the prospect of radical change for the better.

The good news is that there is appetite for such change because people’s consciousness has changed. The hashtag #BuildBackBetter has achieved exponential popularity, becoming a meme for many different people and organisations who see the crisis as offering new possibilities for humanity if we can seize the moment. A YouGov poll, published by the Connection Coalition, found that the number of people who said ‘people in the UK look after each other’ rose from less than a quarter to almost two-thirds between February and May. Similarly, 25 per cent thought ‘it’s everyone for themselves’ in May, compared with 54 per cent in in February.

This change matters because people are beginning to see the importance of social solidarity, which is necessary if there is to be public support for policies and practices to end poverty.

So far so good, but what we don’t have is a coherent roadmap for achieving the kind of change we want. This matters because the forces of disaster capitalism are already organising and are building the world back as it was – just as they did at the time of the 2008 financial crash.

What philanthropy can do

The crisis has confirmed Beatrice Webb’s view that only governments have the scale of resources to address the problems we face.

However, philanthropy has a vital role to play, and is one that governments can’t play. Philanthropy could use its free and patient capital to model a new world. This would involve three main dimensions: (a) to support a new narrative, (b) to support organising to implement the narrative, and (c) to #ShiftThePower in the process. We will take each of these in turn.

Narrative

The first and most important job is to develop a clear, convincing and engaging narrative of what kind of world we want, drawing on the values of social justice and human rights. In an Ariadne webinar in April 2020, Naomi Klein commented on the financial crash of 2008:

‘The Global North failed to put forward concrete alternatives to the failures of neoliberalism. Neoliberalism has polluted our imagination, made collective action suspect. We didn’t say clearly what we wanted. A scattergun approach with 10,000 demands, often contradictory, won’t work.’

Compass is one of the few places where people come together to create the visions, alliances and actions to be the change we wish to see in the world. Their work on welding together work on issues such as the Green New Deal, Universal Basic Income and 45 Degree Change means that some of the main building blocks of a narrative are already in place.

Organise

The next step is to organise around the narrative. History teaches:

‘…as individuals there is next to nothing that we can do to challenge entrenched elite power. Yet, when we come together in collective, democratic movements, we can hold elites to account and take back the power.’[6]

Organising is more than protest. For example, in April 2019, a thousand citizens gathered at Newcastle’s Tyne Theatre & Opera House to ask candidates for election for mayor of the North Tyne Combined Authority whether, if elected, they would work with Tyne & Wear Citizens to tackle issues that local people have identified as most important – hate crime, poverty and poor mental health. Three of the five candidates attended. Labour, Liberal and Independent candidates all signed up to the policies and pledged that they would meet with Tyne & Wear Citizens within the first 100 days in office. Orderly and respectful mobilisation of citizens can bring positive results.

#ShiftThePower

Finally, it is vital to address power head-on, because its absence has a cruel correlation with poverty. Robert Peston, in his masterful WTF?, describes the dehumanising character of our elite-driven top-down society. With high rewards for those at the top, disregard for everyone else has been a key driver of the anti-authoritarian backlash that produced Brexit in the UK and Trump in the US.[7] A study by Hope Not Hate has mapped the consequences of this approach, showing the geographic distribution of people with different social attitudes, which suggests deep divisions at the heart of society in the UK.[8]

If philanthropy is to play a meaningful role in shaping the new world, it is important that it sees itself as part of the activism of the field and accountable to it, rather than merely floating above it in an elite fashion.

To take an example of what can be done, a group of international funders has been meeting in London to consider the implications of the #ShiftThePower movement inspired by the Global Fund for Community Foundations. This involves the new ways of working (for example, through participatory grantmaking, giving circles and community asset mobilisation). A new generation of philanthropies (including community foundations, women’s funds, environmental funds, LGBTQI funds, and national public foundations) is challenging the traditional donor-beneficiary relationship by turning all actors in change processes into donors. These initiatives cast large foundations as equal partners in social advance by bringing resources and agency closer to the people, rather than as a remote elite who control civil society through purchasing specific outcomes through short-life grants. The underlying principle is that philanthropy is for everyone.

Business as usual will not cut it because the formal organisation of civil society is shot through with elitism. An anonymous article written in June 2020 by an international aid worker, who has worked at a senior level for UN agencies and NGOs, notes:

‘White supremacy is prevalent in the aid sector. The vast majority of heads of organisations and senior posts are held by white people – mostly men.’

If we are to #BuildBackBetter, we have to flatten hierarchies, to include everyone and to share resources in ways that reflect the new mood of global solidarity. The time is now.

[1] Coates, D. (2012) From the Poor Law to Welfare to Work: What we have learned from a century of anti-poverty policies, London: Smith Institute and the Webb Memorial Trust.

[2] Based on living in a household with less than 60 per cent of the median income. Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/households-below-average-income-hbai–2

[3] For up to date European data, see https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/pdfscache/29306.pdf

[4] Garthwaite, K. (2016) Hunger pains: Life inside foodbank Britain, Bristol: Policy Press.

[5] https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/jun/03/john-veit-wilson-obituary

[6] Morrison-Knight, J. (2020) How to make elite power listen to the people? Organise, https://www.rethinkingpoverty.org.uk/rethinking-poverty/the-solution-to-the-growing-crises-we-face-organise/

[7] Peston, R. (2017) WTF?, London: Hodder & Stoughton.

[8] Carter, R. (2018) Fear, hope and loss: Understanding the drivers of hope and hate. London; Hope Not Hate

Barry Knight is Secretary to Centris Trustees, a member of PSJP’s Management Committee, a regular contributor to Rethinking Poverty, and Adviser to the Global Fund for Community Foundations.

This post was first published by Ariadne.